When you think of moss, you might picture the old-growth rainforests of the Pacific Northwest or the deciduous woodlands of the muggy Southeast. But moss, though water-loving, can withstand drying out for months or years at a time, only to reanimate almost instantaneously at the first drop of water. Sure, moss looks very different when it’s living in the desert, surviving solely on the moisture of morning dew, than it does on the ever-damp rock face behind a waterfall. But still, it survives.

Mosses were not on my radar as I began exploring Arizona this past summer and fall – I figured they couldn’t withstand the dry heat, as I barely could. The diversity of bees and butterflies, the flashy wildflowers, the jewel-like hummingbirds, the rattlesnakes and speedy lizards, and all the exotic desert plants – these things drew all my attention. Throughout the dry monsoon season, the mosses were undeniably there, even though I didn’t see them – unlike lichen which can remain vibrant blue or yellow or orange even when desiccated, dried-out moss turns a barely recognizable brown or black. In the summer, desert mosses are dark, unassuming smudges on boulders and bark, patiently waiting for rain.

But in wintertime – as the solitary bees lie in wait for spring underground, the cold-blooded reptiles hibernate, the hummingbirds have moved to their wintering grounds in the tropics, and the deciduous trees have long shed their vibrant leaves – the mosses are having their moment. Unbothered by the periodic freezing temperatures, they flourish with the great influx of water brought by winter precipitation, sparkling like emeralds right alongside the snowflakes and sheets of ice. At a time of year when only hardy evergreens cling to their waxy foliage, the soft lushness of the mosses is a sight for sore eyes. They glow with a verdancy you only see along the few rivers that trickle through these arid lands in the summertime. One can’t help but stooping down to stroke them and wondering, how do they do it?

How lucky I am that my favorite naturalist Robin Wall Kimmerer, the author of Braiding Sweetgrass (2013), is also a world-renowned bryologist – one who studies the non-vascular land plants that include mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. Her first book Gathering Moss (2003) contains enchanting secrets of the lives of mosses, conveyed as beautiful stories. It’s not only informative, but an irresistible invitation to fall in love with moss.

As Kimmerer says, there is no such thing as moss, really – there are only mosses, some 22,000 species of them. They can be as different from each other as a fir tree from a sycamore, a ponderosa pine from a coyote willow. There are gregarious generalists and hyper-specialists — some species can be found in the cracks in the sidewalks in every major city on planet Earth, while others only grow on the manure of white-tailed deer dropped by one specific peat bog. A close look at what mosses are doing, at all the different lives they’re living, reveals the entire drama of ecology and evolution in miniature.

Mosses are so-called primitive plants, among the first to move from water onto land some 350 million years ago. They are non-vascular, meaning they don’t have the xylem and phloem tissues which carry water and nutrients up the trunks of trees and the stems of flowers, nor do they have roots to draw nutrients from the soil. This is why they spread over surfaces but remain only millimeters or a handful of centimeters tall— they can only store the water and nutrients they can absorb directly into their cells and hold in the many intricate folds of their tiny leaves.

But this “primitive” limitation is also a strength – mosses can freeze and thaw without sustaining any tissue damage, unlike their vascular counterparts. They secrete their own antifreeze to keep ice crystals from forming inside their cells and bursting their membranes. This is why mosses are found at the poles well beyond where vascular plants can survive, and why they remain so active in the Prescott winters while so many other plants have dropped their leaves or died back.

The smallness of mosses moreover allows them to take advantage of microclimates on the surfaces of things – at the boundary layer between the Earth and the atmosphere, temperatures are warmer, the air is almost still, and humidity is much greater, so moss can hold onto their precious water for much longer. By sacrificing the vascular tissue needed to grow tall, mosses are able to live in much more favorable climactic conditions than the trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants growing right beside them.

What we see as a small patch of moss is a collection of many thousands of individual plants, each with numerous leaves that are a single cell-layer thick, giving damp moss its translucent quality and efficient absorbency. These leaves have intricate folds that create nooks and crannies where water that can’t be immediately absorbed can pool and collect for later use. Every patch of moss is a forest in miniature, home to an entire ecosystem of tiny invertebrates and microscopic organisms like tardigrades (more whimsically known as waterbears), springtails, rotifers, nematodes, insect larvae, and protozoa. Microscopic algae blanket the moss leaves, just as mosses blanket the branches of trees in the forests we walk.

With the right magnifying equipment and microscopes, Kimmerer demonstrates how a journey through a clump of moss can be just as thrilling and surprising and varied an experience as a trek through the Amazon. Imagine the environmental benefit if, instead of flying ourselves around the world to experience exotic ecosystems, we simply grabbed a clump of moss from our backyard and explored what lies within.

I didn’t think my trip down into the desert proper over the weekend would give me any more moss-fodder, but of course, I was wrong. As I pulled into Cholla Campground on the banks of Roosevelt Lake, I found myself in the most lush desert landscape I’ve ever seen. Saguaros and chollas were growing with actual green grasses, clovers, and, of course, mosses at their base. I pitched my tent and scrambled towards the water, where all sorts of mosses, some familiar and some new, were thriving on the rocky shore. And so I learned mosses can be positively verdant not just in Prescott’s pine forests at 6000 feet elevation, but down at 2000 feet in the Sonoran desert, during these rainy, mild winters.

The next morning, I set out into the Salome Wilderness as a volunteer with Wild Arizona to conduct solitude monitoring for the Tonto National Forest. This wilderness area follows Salome Creek, a perennial stream inside a lush canyon lined by magnificent saguaro forests, truly the stuff of dreams. We descended into the canyon to dip our feet in the snowmelt water, and I swear I could feel the blood starting to freeze in my veins after 30 seconds. When I fled to the banks with numb toes, I was greeted by none other than my mossy friends, happily staking out their territory in the splash zone of a perennial desert stream.

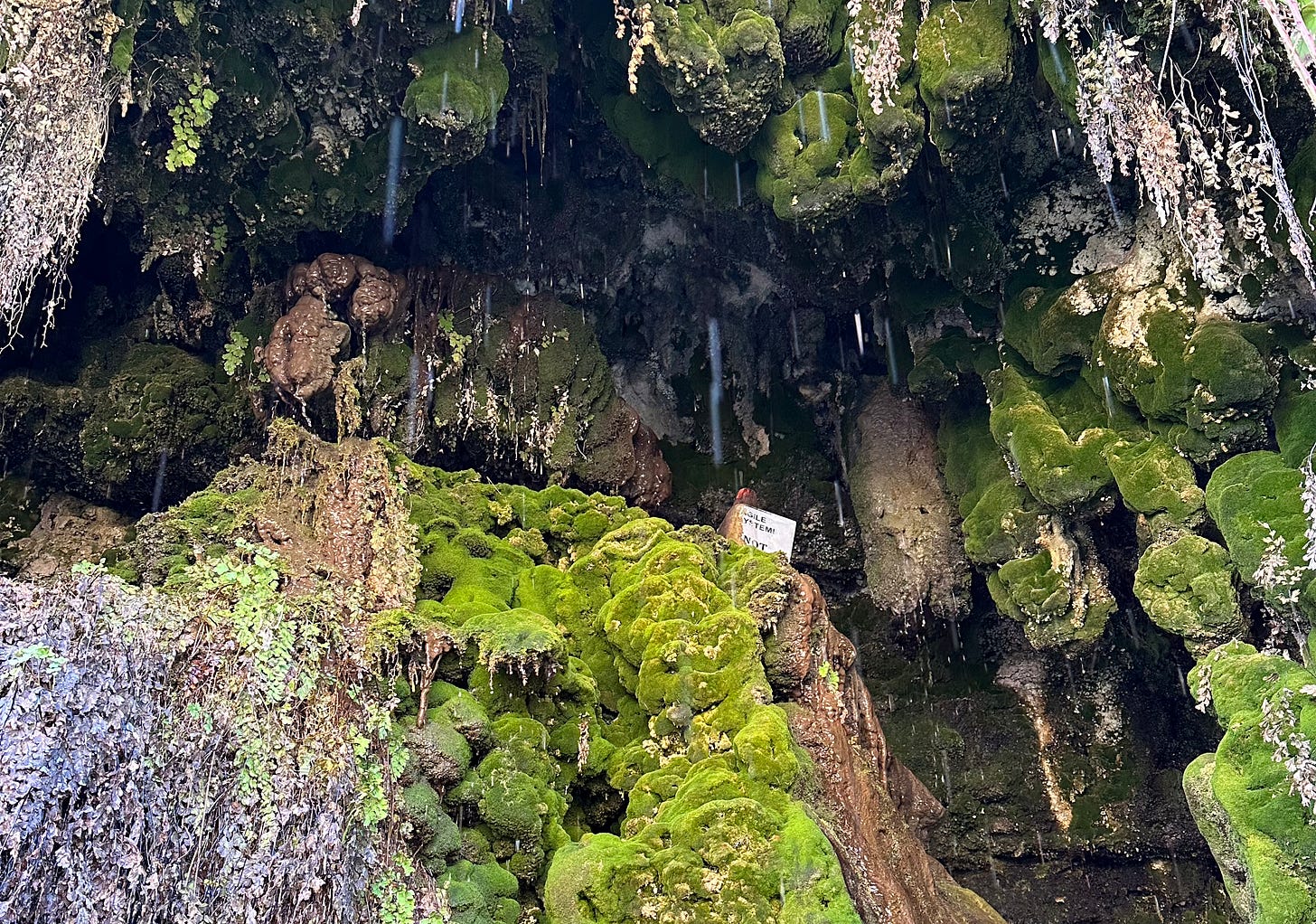

I brought my newly purchased binoculars with me in hopes of observing waterfowl and desert birds. I never expected they would come in handy for mossing, too. On my drive back to Prescott, I made a pit stop at the Tonto Natural Bridge State Park for a couple hours, and as I stood beneath that natural wonder, I saw it as a lesson in mosses’ profound affinity for water. While much of the underside of the bridge is bare rock, the stalactites down which water flows, and the boulders where the water lands, are densely blanketed with bryophtyes, colonies which I imagine have thrived here for the thousands and the even millions of years of running water it took to deposit the calcium carbonate that formed this limestone bridge

With those stalactites in my binos’ view, from hundreds of feet away, I could make out the details of a whole world of wet, happy bryophytes. Not just mosses, but liverworts as well, a far lass common bryophyte with much larger, scaly-looking leaves. I came to marvel at a geological wonder, but the bryological wonder growing right on top of it stole the show. It’s an unavoidable side effect of exposure to Kimmerer’s contagious moss enthusiasm.

Dr. Kimmerer has the remarkable ability to distinguish hundreds of moss genera at a glance, sometimes just from their singular shade of green. Talk about intimacy with nature! Unlike more conspicuous beings like birds and trees, very few mosses have common names, so in order to respect and acknowledge the individuality of each moss being, Kimmerer calls them by their full scientific names. But for those of us who are not career botanists, for whom Dicranum scoparium and Dendroalsia abietina and Polytrichum juniperinum may not roll off the tongue, simply tuning in to distinctions between the types of mosses we encounter can be very enriching in many of the same ways. While knowing scientific names is essential for researchers, what is truly valuable for non-botanists is being able to distinguish and appreciate the subtle details of each moss being, no matter what name you give them. I’m not nearly educated enough in bryology to ID mosses correctly, a very challenging practice that even professional herbariums often get wrong — but that doesn’t stop me from saying hello to the many familiar moss faces I encounter.

Thanks to Kimmerer’s inspiring model, when I think of moss now, I think of mosses – the stalks like tiny fir trees growing beside ferns along the paved path ascending Thumb Butte, the long scaly strands abounding on logs along the creek behind my childhood home, the gritty sprigs in the cracks of boulders along Salome Creek, the rosettes like tiny flowers behind the waterfall at Tonto Natural Bridge, the lime stars and the clumps of blueish-silver tufts I gathered to make my mossarium. I feel a profound sense of connection with the natural world as I note these details, knowing that there is a lifetime of questions to be answered and stories to be told by any one patch of moss. Like getting your first pair of glasses and marveling at the crisply individuated leaves on every tree, it’s a truly new way of seeing the world, through moss-tinted lenses.

To me, that’s what naturalism is about, that’s what poetry is about, that’s what all our strivings are for – taking what we thought we knew and revealing that no, this familiar thing is stranger and richer than we ever expected, with its own stories to tell. In the mosses’ case, these stories span millennia and eons, stretching all the way back to the time when we were all just the latent potential of single cells floating in the ocean, harnessing the warmth of the sun to make the sweet sugars that propelled all life forward.

If I had a hundred lifetimes, I think I’d spend them all practicing delighting in the smallest details of the lives lived all around me. I’m already getting hooked on all I can see now through my new binoculars, which are really just a technological aid in this inexhaustible work of discovering and appreciating the ever-finer details of our world.