Knowing the Birds

A brief history of avian ID

It’s quite jarring to recall that less than 100 years ago, the Western science of ornithology was done primarily by shotgun. The idea that one could describe birds with scientific precision and identify them in the field was preposterous in the 19th century – birds were meant to be studied in the hand, where their morphology could be precisely measured and recorded, not in the bush. Birds were reduced to their qualities as objects, so bird identification came at the cost of a bird death, and formalizing a species account required collecting dozens, if not hundreds, of corpses.

Victorian-Era aristocrats who fancied themselves naturalists funded bird-collecting expeditions to every corner of the globe, where birds were shot by the thousands with no regard for the impact of this practice on local ecosystems. Furthermore, there was no self-reflection on the part of these aristocrats about what entitled them to pillage the fauna of these places they’d never even seen with their own eyes and had no connection to. Birds were collected as indiscriminately and violently as whole continents were “discovered” and claimed, without concern for the rights or needs of the people who already lived there. These birds were shipped back to Europe, stuffed, and preserved to adorn manor houses, to fill out the “cabinets of curiosities” which were an important marker of status and worldliness for the wealthy elites of this era. This is what it looked like to be an “amateur” of birds.

The physical features of birds were cataloged and categorized out of a desire to “master” the unruliness of the natural world, to impose the divine logical order of Western science upon it. The violent, colonial work of these early naturalists laid the foundations of the system we still use for classifying birds today. New evidence from 21st century DNA analysis has shifted some taxonomic lines, and every year some species are lumped together or split in two, but the general structure of classification remains the same. Many common names currently in use reflect the fact that birds were named by people observing their dead bodies – you will likely never see the ringed-neck of the Ringed-neck Duck, for example, unless you are probing the bird’s skin.

At the Natural History Institute, we have inherited a collection of a couple hundred antique bird skins, which were preserved with researchers, not museum-goers, in mind. As such, they have no fake eyeballs, just haunting empty sockets filled with cotton, and they are all arranged in the same streamlined position that makes them easy to store in narrow cabinets. The majority of our specimens were collected on a Biological Survey conducted in California by the US Department of Agriculture throughout the 1930s – so we can say for certain that less than a century ago, government officials were still killing native birds in the name of scientific inventory.

The past century has seen a radical shift in the way we in “the West” study birds and express our passion for them. As I discussed in my last post, we have 30% fewer birds today in North America than we did fifty years ago — this is a catastrophic, deeply concerning decline which it would be unconscionable to contribute to on purpose, even in the name of science. Today in the United States, it is not only illegal to kill any native bird, unless you are a hunter with a permit – it is technically illegal to possess any part of a native bird species without a permit, even one single feather. This seems like overkill, but it’s a well-intentioned and very effective law that has helped many bird populations bounce back dramatically after being hunted to near-extinction in the 19th century merely for their feathers.

What caused this shift towards viewing wild birds as fellow creatures worthy of continued life? I would love to believe it was a triumph of human empathy and a shift towards a conservation rather than exploitation mindset. Around the turn of the 20th century, certain eminent ornithologists like Edmund Selous, author of Bird Watching (1901) and Realities of Bird Life (1927), became outspoken opponents of killing birds, even for science, on moral grounds.

… now that I have watched birds closely, the killing of them seems to me as something monstrous and horrible; and, for every one that I have shot, or even only shot at and missed, I hate myself with an increasing hatred. I am convinced that this most excellent result might be arrived at by numbers and numbers of others, if they would only begin to do the same; for the pleasure that belongs to observation and inference is, really, far greater than that which attends any kind of skill or dexterity, even when death and pain add their zest to the latter. Let anyone who has an eye and a brain (but especially the latter), lay down the gun and take up the glasses for a week, a day, even for an hour, if he is lucky, and he will never wish to change back again. He will soon come to regard the killing of birds as not only brutal, but dreadfully silly, and his gun and cartridges, once so dear, will be to him, hereafter, as the toys of childhood are to the grown man.

Bird Watching (1901), Edmund Selous

This sort of eloquent appeal to the sensibilities of bird lovers certainly played a role in shifting peoples’ hearts and minds. But I strongly suspect that technological shifts – the popularization of portable binoculars, cameras, and the invention of the field guide – were far more important in the explosion of the bird-watching movement in the mid 20th century. Now that we can inspect the details of wild birds with powerful binoculars and take remarkable photos of them at a distance with telephoto lenses, we don’t have to kill them to ensure we can identify them. Birders don’t talk about the kind of morphology you need a magnifying glass or a ruler to observe anymore – we talk about “field marks,” a concept that was created specifically to refer to what one should look for in order to identify living birds in the field.

Essentially, no matter where you travel in the world today, you can find field guides that will tell you all the key field marks for every species you might encounter there. This knowledge, which was largely formalized in the later half of the 20th century, came about through the work of many brilliant birders who often had no academic training in ornithology — instead, tens of thousands of hours of field observations gave them a level on insight into bird life one can only gain through prolonged direct experience.

A great photograph, if anything, tells us far more about a bird than its lifeless body, because a photo can capture habitat and behavior, which are just as important as a bird’s physicality when making an ID. Field marks are not only physical traits – there are many behavioral “field marks” too.

I’m currently taking a self-paced course on raptor identification through Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Bird Academy, an incredible resource for amateur birders. Before we dove into all the minute differences in plumage between hawk species, we started with learning their obvious behavioral differences. For example, Northern Harriers hunt by flying low and slow over open areas, while Red-Tailed Hawks hunt by scanning the ground from a high perch, then dropping down when they lock onto prey. Cooper’s Hawks and Peregrine Falcons conceal themselves in trees and dash out quickly in pursuit of prey, while Zone-tailed Hawks and Golden Eagles soar high above a landscape, scanning for prey to quickly dive down upon.

Without necessarily knowing a single thing about what these birds look like, what they’re doing can tell us a lot about who they might be. Many groups of birds like sparrows and warblers are known for their distinctive songs and calls, which can be far more distinctive than their appearances. Hearing, not sight, is often the most important sense for a birder — birds indeed are far more often heard than seen. Needless to say, none of this invaluable information endures when you shoot a bird out of the sky.

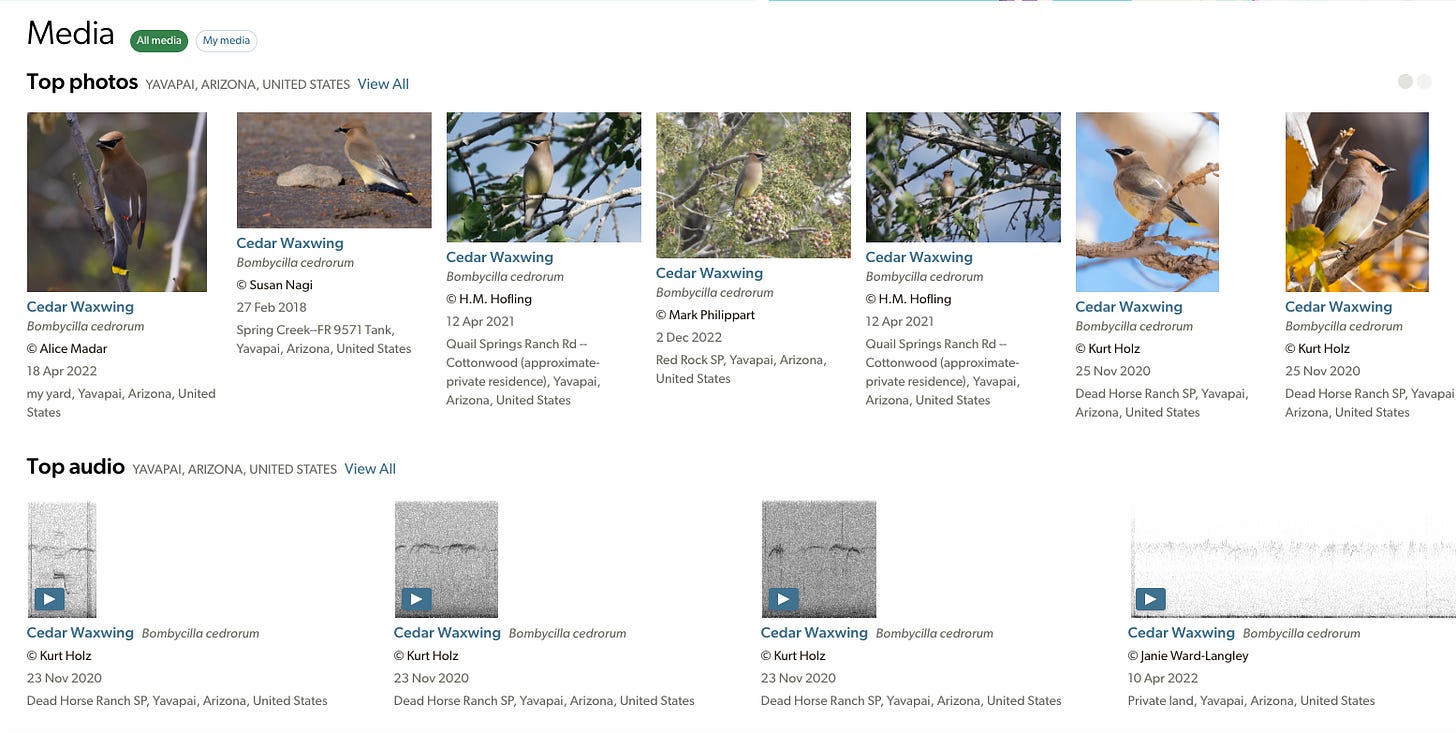

Birding can be (and I’d argue, should be) an exercise in cultivating an intimate connection to a landscape and its community of inhabitants. But it can also be a simple, addictive logic puzzle — the breakneck speed at which information travels and accumulates on the Internet has made it so. From anywhere, I can access eBird on my phone, a database of over one BILLION bird sightings and many, many millions of photographs and vocal recordings, contributed by scientists and amateurs around the world. I now regularly contribute my own sightings to the eBird database which grows every single day.

Thanks to eBird data, I can arrive at a brand new place with a checklist of all the birds that have ever been seen there and know exactly how likely or unlikely I am to see them at this time of year. Birding, done this way, is highly deductive – you begin with the set of all 10,000 some-odd bird species in the world, then move to a subset of the one to two hundred that may exist in a given place at a given time. From there, a bird’s general size, shape, and behavior allows you to deduce its taxonomic category – sparrow, warbler, dabbling duck, heron, etc. – and from this category, the presence or absence of discrete field marks can take you to the bird’s precise identification.

But it’s worth dwelling on how backwards this way of birding is compared to the way humans have interacted with birds for nearly all of our species’ history. On the one hand, until very recently people had no means and no reason for knowing what birds existed on other continents, or even in the next valley or on the next mountain over. On the other hand, they had every reason to know their local birds intimately, to have their own names for them and stories associated with them. The activities of these birds signaled important seasonal cycles associated with the ripening of different food sources. Bird song is rich with meaning about what is going on in our immediate vicinity, which is of particular use to hunters. And some birds were, of course, important food sources themselves. But all this knowledge was born out of great swaths of direct experience with local bird populations that lead to generalized observations about their lives – in other words, inductive reasoning. This knowledge was then passed down through the generations as essential wisdom.

Most of us who now live in places to which we are not Indigenous have fallen out of this ancestral chain of knowledge-sharing, to our great detriment. We can easily go our whole lives noticing just as little about the birds in our backyard as the birds on the other side of the globe.

As amazing as it is to have access to functionally limitless bird data, it’s not any substitute for a wealth of direct experiences with birds, which is endlessly instructive. But the data is nonetheless an entry point into the world of birds that is accessible to anyone who navigates the Internet with greater fluidity than that which we navigate wild landscapes – a statement certainly true of almost anyone around my age and younger.

Since the 1970s, birders have harnessed the swaths of data and of hyperlocal intelligence that the birding community has amassed to make a game out of optimizing their birding practice, competing to set records for “Big Days,” “Big Years,” and the longest cumulative life lists. Travel can be planned down to the minutest detail to maximize the bird species one has the potential of seeing. In the classic birding memoir Kingbird Highway, Kenn Kaufman tells the story of dropping out of high school at 16 and hitchhiking around the country to bird – in 1973, at age 19, he set the record at the time for Biggest Year in North America, with 671 bird species on his year list. Throughout the year, he constantly ping-ponged back and forth across the States and Canada, guided to remote locations by word-of-mouth reports of rare birds from his network of birding friends. Now, one does not even need a personal network of birding confidants to find out about all the rarities – all you need is an eBird account or a Facebook group. Having a Big Year on a global scale is now possible for people with unlimited time and money – the current Big Year record is an eye-watering 6,852 species, set by Arjun Dwarshuis of the Netherlands in 2016.

But we have to ask ourselves, how different are these obsessive listers and birding jet-setters really from the Victorian naturalists I spoke of at the beginning? They are still, in a sense, trying to master the world by putting all its species on their personal life list, by storing them away in the internal cabinet of curiosities that are their own experiences. They may bring money to economies around the world who need it, who can use it to further their own conservation efforts, but at the same time, their presence is necessarily a strain on local ecosystems, a disruption, an encroachment of humans further into wild spaces. Species that are already on the brink of extinction have to deal with the further stress of endless birders trying to see them so that they can get another tick on their life list.

Let me be clear — I would not turn down the opportunity to explore a new part of the world through a guided birding trip, as long as I felt the benefits of ecotourism outweigh the detriments for my destination. Some extreme birders like Arjun Dwarshuis used their mind-boggling feats to raise a lot of money for bird conservation organizations, and I find that very admirable.

But I believe the rewards of getting to know the birds where you live, in your local “patch” as birders call it, go much deeper than the rewards of amassing a huge bird list. It respects bird’s autonomy as subjects rather than reducing them to objects we can collect. It doesn’t just engage this logical, egotistical part of our brains that loves numbers, labels, neat categories, competition, and unending accumulation. It engages our souls, to be doing what people have done since time immemorial – getting to know birds as our neighbors, as fellow creatures navigating life on this earth in community with us, who have much to teach us if we are willing to look and listen.

Just as the people in our lives have their places and contexts and roles, so too with the birds, if we take the time to notice what they are doing. It’s a language that as you learn it gives you the sense of understanding the movements of the world on a deeper level. In my beloved town of Prescott, I know that wherever you come across a certain kind of stagnant muddy pool, there will always be a single Black Phoebe posted up on its banks, hunting for the insects that spawn there. Every time you pass a certain stretch of power lines during the daylight, a little American Kestrel will be perched high up, keenly scanning the ground. When you’re walking through Piñon Pines and Alligator Juniper in the autumn, you are never more than a few hundred feet from a flock of tiny Bushtits conversing in tinkling chip notes. These are all things no one has told me – I’ve found them out for myself through long hours spent outside, just watching the goings-on of the world. I’m liable to forget everything I’m told, almost anything I read, but when I learn something in this way, it sticks to my ribs and stays with me.

This is the kind of place-based knowledge that people pay local guides for when they travel to remote locations to find new birds. It’s a depth of familiarity you only have the time to cultivate with a very limited number of places in your life. But everyone, regardless of their means to travel, is capable of becoming the world expert guide to the birds of their town, their local park, or their backyard.

There are certain ways we can bird watch which are really a continuation of the European naturalist tradition that seeks mastery over the world, and there are others which depart from this tradition, which strive for a harmony with and profundity in nature which has a far deeper human history. I strive for the latter while knowing my experience is indelibly, inescapably shaped by the former, and that I am grateful that I get to have many unique experiences as a birder in the 21st century.

Bird skins, like those we have at my workplace, have largely become obsolete in the ornithological research of today. When scientists have a strong research need to measure morphological and physiological features of a population of birds, individuals are trapped, assessed, banded, and safely released. But when I had the chance to redesign our lobby exhibit at the Institute last month, I thought that our bird skins, despite their unsavory origins and their unsettling lack of eyes, ought to see the light of day rather than remaining stowed away in cabinets, as they still have so much to teach us.

I created an exhibit about avian coloration using these bird skins to illustrate the differences between pigmentary colors, structural colors, and iridescence in feathers. Whether or not they read the interpretation, people are invariably fascinated by the bodies of these familiar birds. Up close, they are always smaller, more delicate, and more intricately constructed than we think they are when they’re sitting on our power lines or flying in a blur overhead. This exhibit attempts to draw attention to amazing details that we often miss about extremely common birds whose existence it’s easy to tune out – like the lovely patch of pink iridescence on the neck of a Mourning Dove, the metallic blue and purple sheen on a Common Grackle, and the neon orange underwing and undertail feathers of a Northern Flicker.

If you are in the vicinity of Prescott, I hope you’ll stop by the Natural History Institute to see the display before it rotates out in early January.

Coming across a bird’s body in the wild unexpectedly, not cleaned and arranged for our eyes in a museum or research context, is another experience entirely. Making sense of these experiences are what set me off writing this piece, in which I amazingly did not address a single one of them. Brava. Those stories will come in a future installment of thinking about bird bodies and bird lives.

If you’re still with me, thank you so much for reading. I appreciate you. And as always, thank you for keeping an eye on things with me.

Enjoyed reading about bird identification. So glad killing birds to study them is in the past (hopefully).

Now that the leaves are off the trees in Illinois - it's much easier to spy which bird is making which noise. Mostly sparrows, ravens and an occassional blue jay or cardinal. I love all of God's creatures.

Thanks for keeping us informed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge and experience! It is always a joy to see and hear what you have been up to now. Your photography skills are expanding in addition to your deeper understanding of the birds. Keep enjoying nature and sharing it with us!