FERAL: A Journal of Poetry and Art just released their 18th issue. Within it, you’ll find a poem of mine called “isolation orange.” I’m delighted to have my work included in this Animal-themed issue alongside so many brilliant poems and striking photos.

Submitting to literary magazines – i.e. grasping at straws for any sense of writerly legitimacy – is a mostly disheartening pursuit. You wait eight months for a two sentence rejection. You find your work has been drastically edited, Gordon Lish style, without your consent, before being published. You’re not that upset when you’re rejected because no one reads these little magazines anyways. No, you ARE upset, since you can’t even get a magazine no one reads to accept you. Womp womp.

So it calls for celebration when you miraculously find a magazine with a perfectly themed issue, and the editors get back to you quickly, and they are obviously cool people because they like what you’re doing, duh. Jaded and lazy, I hadn’t submitted writing anywhere in months, but when I came across FERAL’s call for animal-related poetry in November, I knew I had to throw my hat in. Long before my recent turn towards nature, I have loved writing to and about the creatures of our world, all while plumbing myself for what is most “animal” within me.

Even when a precious acceptance comes one’s way, getting published in one of a thousand small literary magazines can feel like a shout into the void. Or taking a dump into the void? Something like that. That’s one reason why I’m taking the navel-gazing liberty of writing this piece about my own poem – so that it feels a little bit less like nothing at all has happened now that this little piece of my heart and mind has gone out into the world.

Since I was a teenager, I’ve gravitated to poetry-writing as a tool for really getting inside a moment and capturing how it felt from every angle. For many years I wrote poems not to communicate with others, but to communicate with my future self, who is always “other” to present me, sometimes in very radical ways. I wanted to preserve what I could of the irretrievable nuance of my subjective experience, and words were my tool of choice. I did it for myself entirely – the idea of sharing what I wrote horrified me deeply, and rightfully so. I was laying myself bare in those poems, in all my glorious adolescent angst.

Through studying poetry for my degree and taking some formative creative writing workshops, I learned to think about what poetry can do and how it works much differently. I figured out how to better obscure myself in my poems so that something deeper, more subtle, and unique to poetry could be revealed in the process. As I recently heard the poet Jane Hirshfield say in a webinar, poetry preserves the wisdom of interiority — writing poems helps me give some form to this initially voiceless wisdom.

I know that there’s nothing more frustrating and less appealing than reading a poem you don’t understand, and I sense that this poem I have published is not an easy poem to grasp, especially for anyone not already invested in poetry.

I absolutely don’t think anyone is obligated to care about poetry – but I know there are people reading this who care about me, who want to understand what I write, who may find this poem baffling. So for those people, and anyone interested in my poetic thought process, I humbly offer up this reading of my poem “isolation orange.”

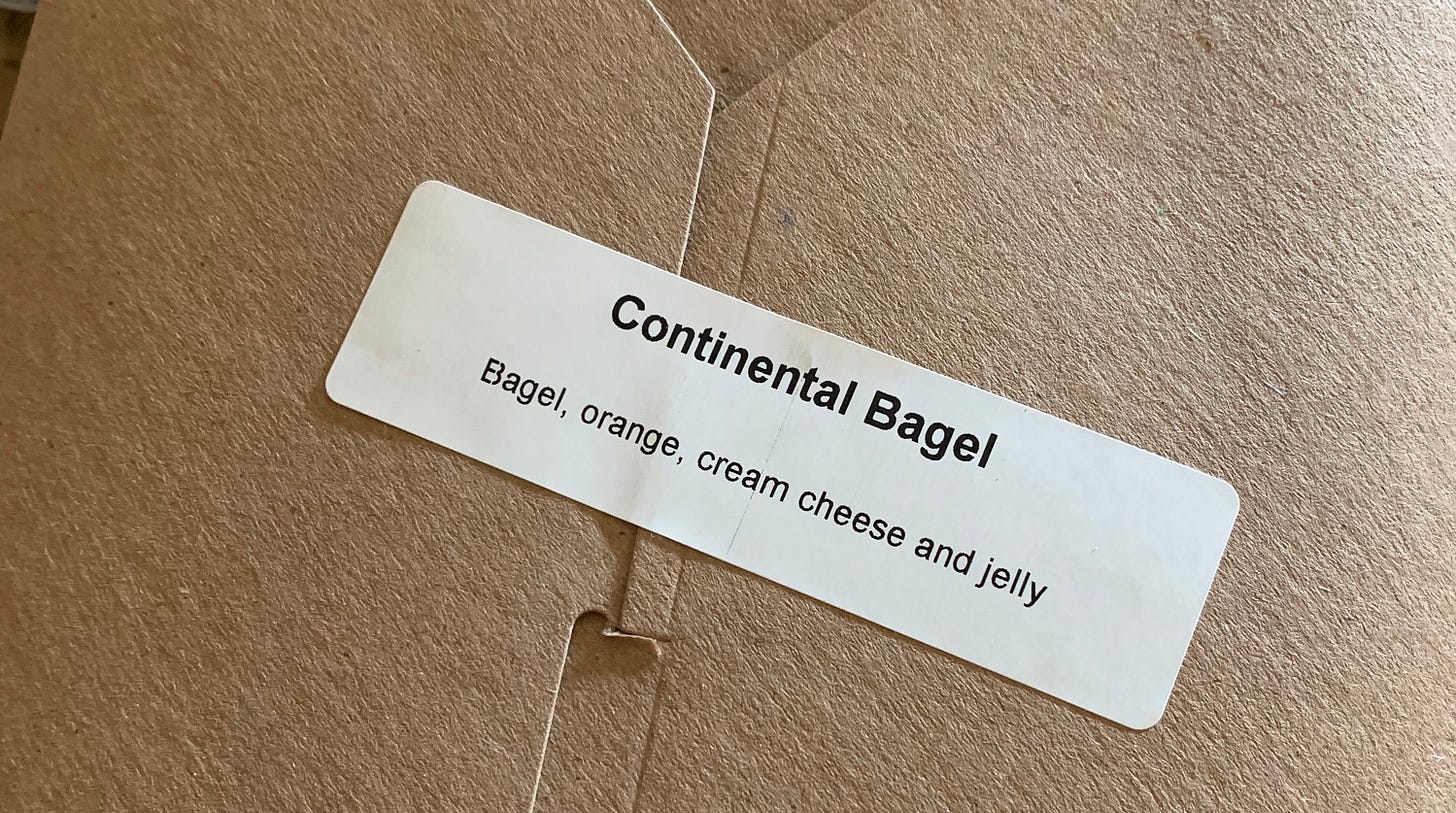

I wrote “isolation orange” when I had Covid for the second time in April 2022. On the auspicious day of 4/20, I received my positive test result and was whisked away to isolation housing on Stanford’s campus, my own sleek empty apartment I was not allowed to leave for a week, with dining hall food delivered directly to my door. Everyday in my breakfast box, along with a dry bagel I had no toaster for, there was an orange, a fruit I never usually eat because I find them so damn hard to peel.

But it was what I had for breakfast, so I ate my orange every day, slowly and with relish. I hardly bothered with the flimsy plastic knife that was my only tool. It became a ritual, sitting at my fifth-floor window and messily consuming my orange while looking out into the courtyard below where people on bikes or dogwalkers would sometimes pass through.

I was in a poetry independent study at the time with my amazing mentor Austin Smith, and I was scratching my head over what I could possibly be drawn to write about inside these four white walls. It was the banality of eating an orange at the window that felt more and more like an Event each passing day. It was the brief respite from the hours and hours of staring at screens and pages, my gaze never more than a few feet in front of me. It brought me back into my body, turned my gaze outwards, and made my poetic senses tingle.

As I ate my orange, I felt I was not a separate observer but a part of the whole scene, the collection of actions that make up the happening of life. That is why, even though this is a poem about what I was doing and seeing in a moment, there is no “I” and nothing is “mine.”

sunlight sacs never stay intact

so the juice drips down the wrist

and settles stinging into tattoo ink

When I write a poem, I’m guided by sound as much as meaning – the words are meant to be read aloud or at least heard with your inner reading voice. This first line, with its alliteration and consonance, created a rhythm I immediately wanted to pursue.

The “sunlight sacs” are all the tiny vesicles of liquid that make up an orange, which were constantly bursting all over the place as I ate. The juice of an orange is delicious and sweet when it enters the body through the mouth, but in a wound, or in the eyes, it stings – I wanted to explore the dark side here, the sting.

skin rips, pith sticks beneath the nails

gone purple-pink from lifetime lack

of oxygen, peeling yellow at the tips

As a lifelong nailbiter of a pathological degree, I have always had a fraught relationship with my hands and fingers. You will never see me describe them fondly. Picking at the orange satisfied that same urge I have to pick and peel at skin, and the ragged state of my nails made its grit stick to me and the juice sting.

I love the word pith – I love how it sounds and I love that we have a word for something so specific as the white stuff between the peel and the juicy insides of a citrus fruit. When we have a name for something, we can tune in to it. One of my favorite things to do in a poem is to really immerse myself in a different vocabulary – in this poem, that was all the words we have for very specific parts of fruits.

pulp catches between gnashing teeth

hunched monkeylike at the radiator

thumbing carpels to the cheek

More citrus words – pulp, carpels (the word for each segment of an orange).

I did feel like a primate, wordlessly and messily imbibing my daily fruit. But I also felt dispersed, and referring to body parts unattached to a subject – gnashing teeth, the cheek – grasps at that sense of my body being an event, some action making up the whole scene of the window sill, the room.

the pic pic pic of a white ball chain

which opens and closes the eyelids

a gaze and a wave whiz past each other

The eyelids here are not my eyelids but the curtains – the eyelids of my window, my point of contact with the physical world outside. Through these eyes sometimes I would wave to someone that I thought saw me down below, only to release they didn’t see me at all.

a fly flits dizzily, tracing a triangle

like he’s trying to square the hypotenuse

drawn by a bursted follicle

Follicle! Another word for the little juice sacs in an orange. Flies would enter my room through the window, and I felt the weight of their presence like I never do in normal circumstances. I noticed one flying in what seemed like very precise shapes, whose purpose was incomprehensible to me. This was my attempt to get inside a fly’s mind and imagine what that purpose might be.

perhaps letting the rind drop a dog

would mouth it like a shredded tennis ball

and the sticky sill become a sanctuary

Starved for fresh air and company, I imagined weird ways I might illicitly engage what was outside my room. I wondered what would happen if I simply chucked the orange rind outside and watched who took it up. I’m proud of the last line — its alliteration, that magnificent word sanctuary, its encapsulation of the whole scene. In my first draft it was in the middle of the poem, but Austin wisely urged me to let that line have the final word.

I was surprised and delighted to see that the editors of FERAL paired my poem with a photo of an adorable dog mouthing a tennis ball, by the very talented photographer and professor Max Cavitch. The sweetness and gentleness of that image contrasts with so much of the poem’s harshness, yet it makes this crucial final image sing.

I hope my commentary has given you a bit more to sink your teeth into with this poem. A poem certainly should speak for itself without needing any commentary to move people, BUT, also, poetry is weird and confusing! I don’t think I would ever have written something like this if I hadn’t spent a lot of time reading poems closely, discussing them in class, and trying to wrap my head around how they work, which I know is not something most people have had the luxury of doing.

I’m sure it’s blasphemous to some poets, but I find it rather exciting to explain my choices in a poem and shed some light on the context of certain images. It’s through this exercise, whether in workshop or in my independent studies, that I have learned to write more impactfully. It’s not the same as analyzing someone else’s poem, but it’s not as different as you’d think – I feel like a completely different person today than the one who wrote this poem, and it’s been a delightful exercise to revisit it with fresh eyes. That is the one upshot of the extremely slow process of submitting to literary magazines.

You may be left wondering what the value is of the poem by itself, given how much comes to light with some context and elaboration in prose form. But what I’m doing here is mere window dressing to what a great poem does all by itself.

The best poems I have encountered are inexhaustible beyond any possible interpretations – they show you a new way to see the world every time you read them. As Gaston Bachelard wrote about extensively, they free our minds by making the familiar fresh and strange, launching us into daydreams. You feel in your bones that not a word is out of place in them, even if you can’t articulate what each word is for.

Obviously I could never make that judgement about something I wrote. But I know that this experience exists, as I have had it on many occasions reading other poets. I hope showing you some of the behind-the-scenes of my poem, which can seem haphazard and obtuse at a glance, may inspire you to spend some more time with the amazing poems in this issue of FERAL. It’s utterly humbling how much richer so many of them are than this one.

You can access all of FERAL’s issues for free online, including the Animal issue, which will soon be available in print as well. I’ll tip you off in a future newsletter in case you’d like to purchase a hard copy and support this small literary magazine creating a wonderful platform for artists and poets.