I’ve never been one for the hypothetical questions beloved by teenage boys about which of two fearsome animals would win in a fight. And yet, after a week on Central Florida’s Rainbow River, encountering an enchanting array of wildlife, I can’t stop thinking about who really rules those waters – the gators or the otters.

Watching the wood ducks set me off on this line of inquiry, for they did not react to the appearance of either creature as I expected they would. If I’ve learned one thing from the wood ducks, it’s that we have it all wrong about gators and otters. The question of which one is the apex predator does not have the clear-cut answer you would think.

The Rainbow River bubbles up in Dunnellon, Florida from Rainbow Springs, a collection of vents that release 400-600 million gallons of crystal clear water from an underground aquifer every day. The resulting river winds for 5.7 miles before feeding into the Withlacoochee, which flows 141 miles into the Gulf of Mexico. This perennial water source is the foundation sustaining the complex and diverse ecosystem that allows American Alligators and American River Otters to co-exist.

The river is lined with lush underwater beds of strap-leaf sagittaria and eelgrass, whose blades undulate in the current like a mermaid’s locks, providing food and coverage for all sorts of aquatic invertebrates and fish. Cypress trees tower with their trunks and roots submerged, shooting up numerous knobs called “cypress knees” above the waterline. Upon the sandy banks, enormous pines, elegant magnolias, and sprawling, gnarled oaks grow blanketed in Spanish moss. The fronds of native palm trees arc and droop towards the turquoise waters.

This veritable cornucopia of vegetation, insects, and fish is ideal habitat for many different kinds of birds, with something to offer for every nesting preference and dietary niche. The wood ducks and gallinules munch on floating mats of vegetation, the herons and egrets stand still for hours waiting to pounce on fish from above, cormorants and anhingas dive like torpedoes to snatch prey underwater, ibises probe holes in the banks with their dainty bills, ospreys snatch up large fish in their powerful talons, and black vultures feed on whatever carcasses remain.

Aquatic and semi-aquatic turtles find a haven in these waters as well, with pond sliders, softshells, snappers, and many other species observable at every bend. These omnivores sunbathe on the numerous large rocks and fallen logs that protrude from the water, when they are not paddling around foraging for plant matter, aquatic insects, crustaceans, small fish, snails, and amphibians.

At the top of this rich and intricate food chain, enter the otter and the gator.

One is an adorable, puppy-faced mammal known for its extremely soft, water resistant pelt and playful personality, whimsically depicted holding hands or taking a cat nap while floating downstream. The other, with its leather-tough scales and terrifying bite force of 2,000 pounds per square inch, is regarded as a real-life swamp monster – menacing, evil, soul-less, likely to snack on a person given the right opportunity.

But despite our vastly different perceptions of these two creatures, both are essentially opportunistic carnivores, capable of terrifying stealth attacks, known to eat any kind of creature they can sink their teeth into. Otters, as well as gators, are apex predators in most of the places they occur, although they only weigh 30 pounds to an adult gator’s 1,000. They make up for their small size in cunning, ferocity, and teamwork.

I spent much of my week on the Rainbow River, at the house of family friends’, sitting on the dock or on the screen porch with my binoculars, trying to decipher the affairs of the animals around me. There were always many wood ducks around, in their duller eclipse plumage but still striking with sleek crests and white eye rings. They were constantly sunning on the neighbor’s dock, dabbling in the reeds, and enjoying bird seed scattered for them on the lawn. I learned two surprising things about wood ducks during this week. They trust gators, and they despise otters.

The first time my mom spotted our local gator while out on the dock, he was making a bee-line, albeit very slowly, right towards our beloved flock of wood ducks, with fuzzy ducklings in the mix. We thought we were about to witness a moment straight out of National Geographic.

Only his obsidian eyes and a small stretch of dark green plates on his upper back peaked above the water line. His monstrous, pre-dinosaurian form cut quietly through the wakeless surface. But the ducks did not panic. They did not squawk or flee by half-flying, half-walking across the water, splashing up a ruckus, as they did when I let the porch’s screen door clang shut too loudly. What gives? I wondered. I feared they didn’t notice the stealthy gator, so we screamed and waved our arms at them, watch out, you little idiots! But the ducks knew better than us. Of course they knew he was there. The gator glided peacefully past them, and turned into some hideaway in the reeds.

Not long after, I spotted a band of three otters paddling their way upstream. With much greater mirth, we gathered on the dock to watch them bob their furry heads and dive back down under the water like dolphins. Once they were parallel to the dock, they dove deep and we lost sight of them, until some ducklings and their mama started screaming. Half of them scattered towards the shore, onto our neighbor’s dock, and half scattered into the cover of the seagrass that lined the opposite bank. An otter head surfaced where the ducks had been, then disappeared beneath the surface again. The otters had tried to ambush the birds from underneath, hoping to grab a quick duckling snack. Some of the poor, terrified babies were separated from their mother in the ruckus.

Once they accepted that they had missed their shot, the otters continued upstream, but the ducks didn’t return to the water for another 20 minutes.

On the other hand, it became apparent throughout my week in otter and gator country that the wood ducks don’t just tolerate gators – they seek out their presence. On a float from the headwaters several miles back down to our dock, we found a duck haven on the more secluded side of a small island. There, dozens of ducks rested in the shade, concealed from the heat of midday and the hoards of rambunctious floaters in inner tubes, yayhoos that dropped in at the Rainbow Springs State Park. At the duck haven I saw my first baby gallinules, who are covered in black fuzz save for their reddish bald heads that make it look like their brains are on the outside. Like freshly newborn humans, they look a bit like aliens.

But from my kayak the following day, I was shocked to see that right in front of the island, our gator was hanging out in the water, just feet away from ducks taking their afternoon naps, with their heads tucked into their bodies. Some of the ducks swam right by him nonchalantly on their way on and off the shore. They let their guard down far more than I would in the presence of an adult gator, while being a hundredth of my size.

The strangest spectacle of all came that night, when that gator made his way from duck island back to the reeds across from our dock. He was escorting a whole procession of ducks! So they not only let him hang around – they wanted to be near him!

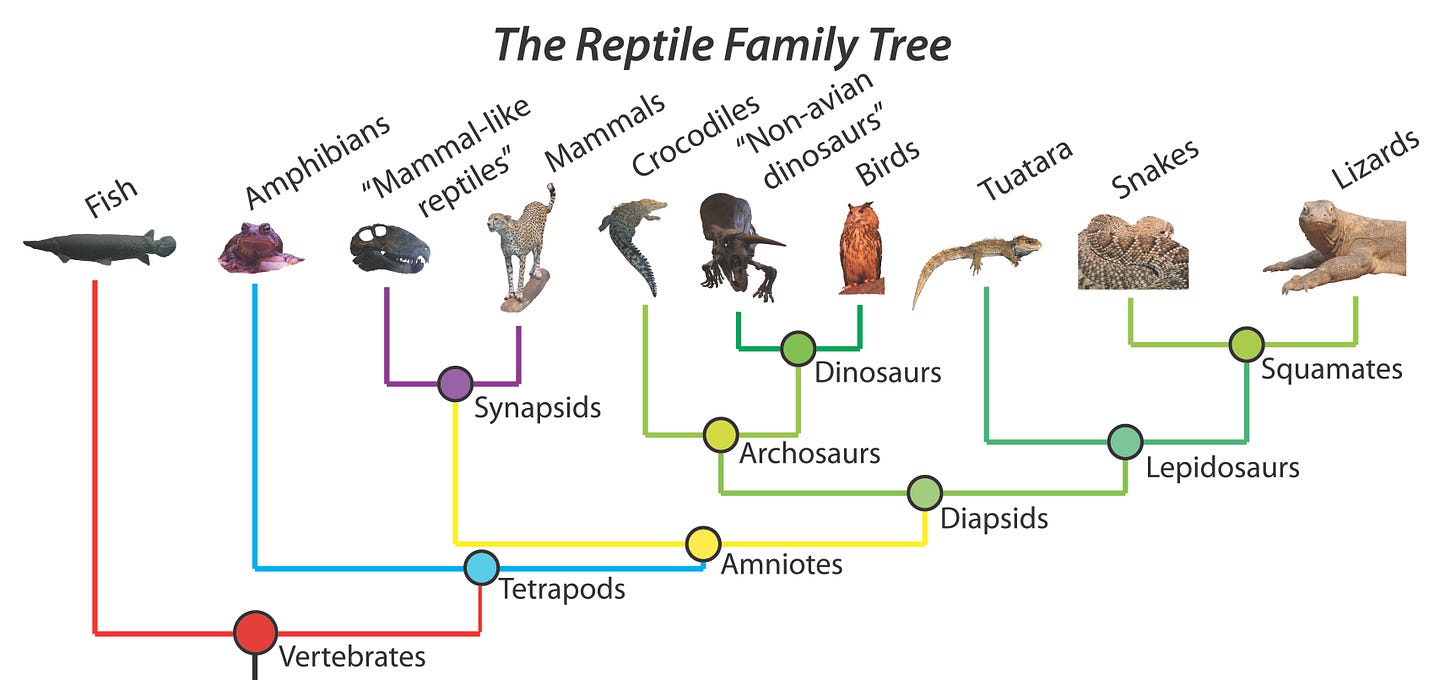

From an evolutionary perspective, birds and alligators are in fact each other’s closest living relatives. They diverged from their common ancestor, the archosaur, about 240 million years ago. This is a very long time ago, but it still makes alligators more closely related to birds than they are to lizards, snakes, turtles, and all the other scaly creatures we recognize unquestionably as reptiles. This leads us to the strange reality that birds are technically reptiles – there is no way to parse out a family tree that includes all of the modern reptiles and extinct dinosaurs while excluding birds.

Is their evolutionary kinship what makes waterbirds and alligators strange bedfellows? Could be. Probably not. More compelling is the emerging ecological explanation for this phenomenon of birds associating with alligators.

While I wasn’t able to find any studies that specifically tracked the association of wood ducks and alligators, there has been excellent research done in Florida specifically on the tendency of long-legged wading birds such as herons, egrets, and ibises to nest near alligators. These birds nest colonially, and it has long been observed that there always seem to be resident alligators near these nesting areas.

This isn’t simply because alligators are attracted to bird colonies as a source of food. In a 2017 study from the journal Wetlands, Burtner & Frederick found that colonies of wading birds always choose to nest near alligators when given the choice between sites that have alligators and sites that do not. Even adding an alligator decoy to waters without gators made birds more likely to choose that nesting location.

The birds are clearly benefiting from the alligator's incidental role as a protector animal, warding off nest predators like raccoons, who can wipe out an entire clutch of eggs or nestlings in one fell swoop. This is well worth the reality that the alligators do end up eating a fallen nestling or two from each nest. Those were probably the weakest nestlings who would’ve succumbed to other threats anyways. It’s a harsh world out there for wild birds.

A 2016 study in the Florida Everglades further found that the alligators were benefitting measurably from this relationship, too. The researchers concluded that alligators who lived near a bird colony were in better health across multiple metrics and had greater body mass than alligators who did not.

I find it amazing that even between predator and prey, mutualism can arise. My hypothesis, which I would love for someone to test, is that wood ducks are also using alligators as protector animals, not to ward off nest predators, but to ward off the otters that terrorize them given the chance. The gators probably do eat a duck here and there, but for the ducks, the protection they receive is worth this occasional sacrifice.

Now, I don’t know of any examples of otters engaging in this sort of mutualistic relationship with other species. Even relations between wild otters are known to be brutal — death by sexual trauma is shockingly common for female otters, and necrophilia, kidnapping, and killing of otter pups in order to obtain food and mating opportunities is regularly observed in otters. It’s heinous stuff. When many otters do live cooperatively, it is usually in the off-breeding season, for the purposes of hunting more efficiently together than they do alone.

Few would expect an otter to escape with its life in a fight with an alligator. But sometimes, they not only live, but get a fine meal out of the encounter. For one, baby alligators are an easy meal, not only for otters, but for almost every carnivore in the wetlands, including other alligators. They are only eight inches long at birth, adding a foot to their length every year for their first four or five years. Alligator mothers, unlike most other reptiles, provide extended maternal care, staying with her hatchlings for at least their first year of life. But even with their fearsome mother providing protection, only about 5 alligators hatched from a typical clutch of 38 eggs will survive to adulthood, and this portion only gets smaller as population density increases (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission).

But even an alligator that is as long as an adult human can be taken down by an otter who has learned the right strategy. Despite being so much smaller, otters have a great stamina advantage against gators, who can move quickly and with great power in small spurts, but tire out very easily. In 2014, a visitor to Florida’s Lake Woodruff National Wildlife Refuge photographed an otter taking down an impressively large gator by biting the back of its neck and holding on for dear life. Their bite force is three times as strong as a pit bull’s, an astonishing force for their size. The gator thrashes itself into exhaustion within a matter of minutes, and the build up of lactic acid in its muscles kills it. Then, the otter can drag it to a safe place to chow down.

This is why there is no clear predator-prey relationship when it comes to otters and gators – a gator can take an unsuspecting otter, of course, but otters can wreak havoc on a population of young gators and even nab a sub-adult if they’re smart about it.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimates there are 1.3 million American Alligators living in their state – holy sh*t, that’s 20 gators every square mile! But between 1948 and 2022, there were only 453 documented alligator attacks on humans, with 26 resulting in fatalities. Sure, this is more people than otters have killed, THAT WE KNOW OF. But given the density of alligators, in a state not exactly known for its mild-mannered, respectful habitants, I find this an astonishingly low number. You are exponentially more likely to be injured or killed by somebody’s domestic dog.

Otters haven’t killed anyone yet, but they seem more than capable of doing so one day, especially as human development continues to encroach on their turf. In the late summer and fall of 2023, there was a well documented string of otter attacks on human swimmers in lakes and rivers in northern California. One 69-year-old man suffered 40 puncture wounds in a multi-otter attack while swimming just outside his own home.

If I were a duck, I would certainly try my hand with the gators rather than the otters. The gator is not going to expend his limited energy uselessly, just for the sake of violence or to nab a quick and easy snack. But the otter is an indefatigable force of chaos.

So what’s the point of all this talk of terrorist otters and protective gators? I guess, that all creatures contain surprising multitudes. Otters can be fearsome and terrifying, and gators can be gentle and nurturing, and birds can make clever, calculated wagers with their own lives and offspring. All wild creatures merit our delight, not just the cute furry ones, and all ought to be observed with caution and at a reasonable distance, not just the enormous, scaly ones.

Fear the otter. Love the gator. But most importantly, respect them both. And as always, thanks for keeping an eye on things with me.

Thanks for the lesson on otters (and alligators). I always thought the river otters we have in Central Illinois were so cute and smart. Now I'll be leary of them. No worries about gators in our neck-o-the-woods - but don't tangle with an otter......

I know your family loves their retreats to the Floridian river paradise, but I didn’t realize the diversity of wildlife down there. I have had only one experience with river otters and one experience with an alligator. Your great-uncle released river otters in central Illinois to re-introduce what had been a native species whose populations were decimated by habitat destruction and hunting. As a wildlife biologist, he was charged with holding onto six or so river otters that he was transporting in his state truck. I can’t recall what exactly the enclosures were (maybe big pet taxis), but those river otters sounded downright evil in the back of his enclosed bed. They hissed like little demons, not that anyone could blame them. They were not cute and fun loving in that environment. The alligator, on the other hand, was one we stumbled upon, practically, on some island park we visited many years ago in Florida. We were walking on a nature path and noticed it resting just a couple of feet away from us. It was startling to us, to say the least, but it had no interest in us. I will say there was signage warning of gators, and I was thrilled (and a little scared) to encounter one so close. Thanks for sharing your wonderful observations and, as always, I love your writing!